A version of this appeared in the Journal of Commerce on March 26, 2020

There is no doubt that we are in the midst of supply chain disruptions that will have global implications for many months – regardless of the time required to bring COVID-19 under control. The lion’s share of that impact will be felt in international trade lanes – especially for containerized freight.

The transportation industry has experienced its share of supply chain shocks: the 2008-2009 recession, the 2012 longshoremen strike, the aftermath of floods and hurricanes, and the intermodal capacity crunch of 2018. Yet the shutting of international borders and quarantines of entire countries is something new.

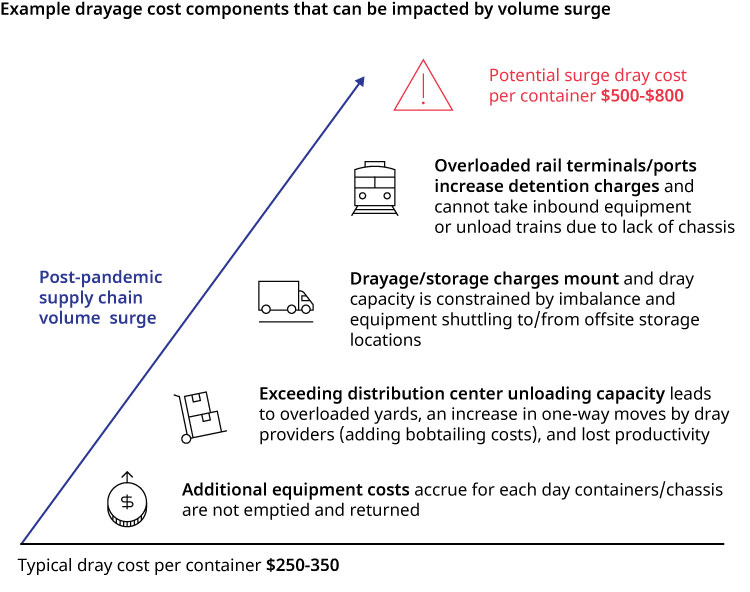

Organizations are working around the clock to develop and implement short-term crisis management plans. But another obstacle looms large in the form of the surge-back of freight that will occur when the supply chain is fully reengaged. Based on past experience, in North American markets, any rush to return to normalcy could lead to the doubling or tripling of inland transportation costs per container, while transit time and reliability could degrade as capacity tightens for key resources (chassis, terminal space, drayage). Both shippers and transportation providers will need to plan ahead and plan differently to avoid seeing inland transportation networks disrupted once more by volume-spiked congestion and displaced assets…

Read the rest of the full article on the Journal of Commerce website.

Exhibit 1: Drayage Costs Can Double Or More With Supply Chain Surges

Source: Oliver Wyman analysis