Update: 5/4/2017

The American Health Care Act (AHCA), which narrowly passed the House on May 4, aims to repeal many of the ACA provisions related to the individual insurance market. One of the more significant changes is the way premium subsidies would be determined. Under AHCA, subsidies would be provided in the form of fixed tax credits, with the amount of credit based on an individual’s age, not income, for anyone earning up to $75,000 per year.

According to analysis by Oliver Wyman’s Actuarial Practice, this change will translate to lower net premiums for most younger adults and significantly higher net premiums for lower-income older people. (The Congressional Budget Office Cost Estimate released March 13 also concluded that older people will face higher premiums.)

The Oliver Wyman analysis also finds that rural enrollees will generally pay higher net premiums than urban enrollees of the same age and income levels, as The Wall Street Journal reported in a March 13 article based on our work.

Note: The amended version of AHCA, which contains additional funds for high-risk pools and grants state's the ability to waive some insurance rules of the ACA, has not yet been scored by CBO. The below analysis is based on the original form of the bill.

Nonetheless, it is critical that all stakeholders understand how health reform may impact net premiums in their local geographies. Markets that face significant net-premium increases, as well as markets with a higher prevalence of lower-income, older, and less-healthy populations could potentially see an acceleration of adverse selection. That would have the potential to create unsustainable insurance pools and higher uncompensated care.

Here, Dianna K. Welch, FSA, MAAA, and Kurt Giesa, FSA, MAAA, of Oliver Wyman Actuarial Consulting provide more information on the premium analysis, including a detailed look at what the replacement plan means for individual health consumers in select markets.

Subsidies under ACA

Under the ACA, subsidies are calculated based on the net premium an individual is deemed to be able to afford based on their income. For example, someone whose 2017 income is 200 percent of federal poverty level (FPL) – that’s about $23,760 – is required to pay 6.43 percent of his or her income for 2017 coverage. That translates to $1,528 a year, regardless of a person’s age.

The amount of subsidy is the difference between the affordability amount and the premium for the second lowest-cost Silver plan available. For example, if the second lowest-cost Silver plan costs $2,000 a year, the difference between cost and affordability is $472, and the subsidy is about $40 per month.

People who face higher gross premiums, due to their age or due to living in a more expensive market, receive larger subsidies to get the net premium down to the level deemed affordable. If the second lowest-cost Silver plan in an expensive area of the country is $2,500, the difference between cost and affordability for someone earning 200 percent of FPL is $972, and the subsidy is about $81 a month.

Subsidies under AHCA

Under the AHCA, subsidies in 2020 will take the form of a fixed tax credit, and the formula for determining the amount of the credit is based solely on age for anyone earning up to $75,000, or about 600 percent of FPL. The amount a person will be required to pay out of pocket – the net premium – is calculated as the difference between the premium charged and the subsidy amount received.

The following tables summarize the amount (in percentage of income) people currently pay for health insurance under the ACA and how much people would receive in tax credits under the AHCA.

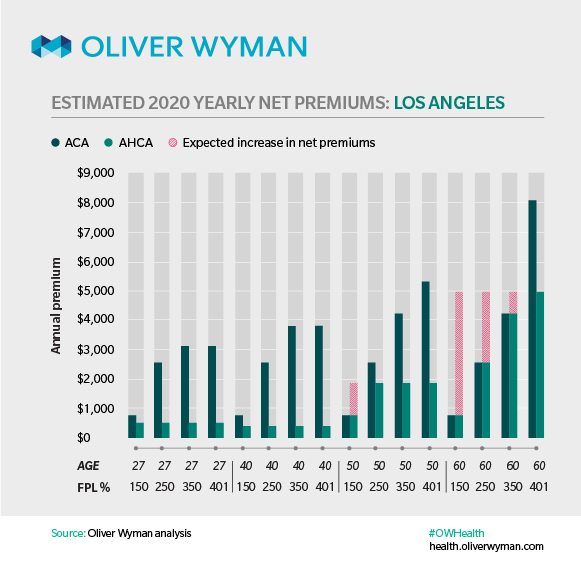

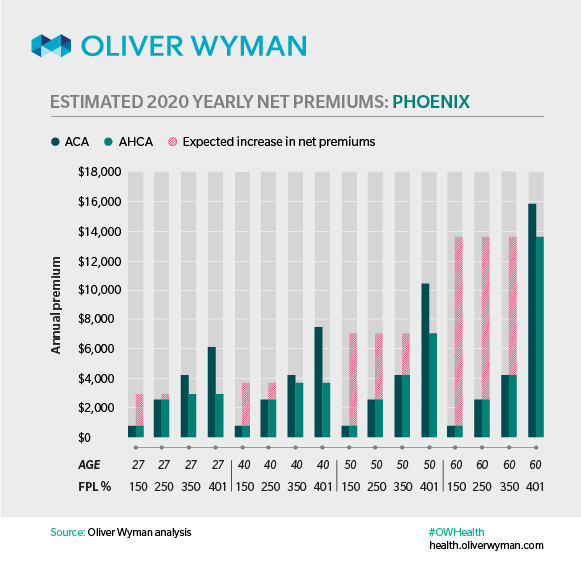

How individuals would be impacted: A look at two cities

To understand the impact of this proposed change on individual health insurance consumers, we projected premium rates for enrollees in two cities: Los Angeles, a relatively low-cost market, and Phoenix, a relatively high-cost market. We calculated the future costs by taking the 2017 premiums for the second lowest-cost Silver plan in each city, and then projecting those premiums to 2020 under current law. Applying the proposed subsidies to our projected 2020 rates, we are able to estimate the net premiums for enrollees in these two cities.

In our analysis, we also relaxed the age-rating band. Under the ACA, age-rating bands prevent insurers from charging adults 64 or older more than three times the premium they charge younger members for the same plan. The AHCA increases the age-rating band to 5:1, which will result in premium increases for older adults and premium decreases for younger adults, all else equal. Our analysis projected premiums under the AHCA using 5:1 age-rating band.

We found that in Los Angeles, many age groups and income levels will see a drop in net premiums under AHCA, but that older low- to middle-income individuals would face higher costs. For example, a 60-year-old with an income level of 150 percent of FPL (roughly $18,000) would pay approximately $4,000 more a year in premiums under AHCA, while a 60-year-old with an income 350 percent of FPL (roughly $42,000) would pay about $1000 more.

Younger people would see their net premiums drop. For example, a 27-year-old earning 150 percent of FPL would pay $300 less a year, while a 27-year-old earning 350 percent of FPL would pay roughly $2,500 less per year under the AHCA than under the ACA.

In Phoenix, most age groups and income levels would see net premiums increase, with low- to middle-income earners facing the greatest increase. A 60-year-old earning 150 percent of FPL is projected to pay $13,000 more per year for similar coverage under AHCA, while those earning 350 percent of FPL would pay $9,500 more.

Young adults, and those with incomes greater than 400 percent FPL (up to $75,000), would benefit from lower net premiums. A 27-year-old earning 350 percent of FPL would pay $1,500 less, and a 27-year-old earning over 400 percent of FPL (but no more than $75,000) would pay $3,000 less.

The AHCA maintains the concept of a state-based, single risk pool. This means the premiums individuals pay in any given state are based on state-wide experience. Our projections exclude any potential changes to the health of the overall state-based risk pools. For example, if a larger proportion of sick people enroll in coverage in a given state as a result of the AHCA subsidies, costs would increase, and consumers could expect higher premiums. Alternatively, if a larger proportion of relatively healthy individuals enroll in a state, premiums in that state would decrease.

We believe that it is relatively safe to assume that in Phoenix, those most likely to enroll – in the face of significantly higher net premiums – will be those in poorer health, as those in good health may not see enough value in the higher net cost of coverage. If that were to occur throughout Arizona, it would lead to even higher premiums than those modeled here. Meanwhile, the opposite may occur in Los Angeles, where net premiums become more affordable for most age and income groups. If that were to occur throughout California, premiums would be lower.

The question for policymakers and issuers

Whatever form AHCA may take after debate and mark-up, one thing that’s certain is that stabilization of the individual market hinges on keeping and attracting relatively healthy enrollees. For state-based policymakers, that includes understanding how their state should use its share of the $100 billion from the proposed Patient and State Stability Fund. For issuers, they will have to be in a position to react, through benefit design, network configuration, marketing campaigns, etc., to what is likely to be a pronounced shift in the make-up of the market, to one that is younger, higher income and more concentrated in areas with lower costs.

Note: Oliver Wyman did not analyze every factor that could have a material impact on health insurance premiums and coverage. Additional factors that could influence premiums and coverage include the elimination of cost-sharing reduction payments in 2020, the proposed Patient and State Stability Fund, and potential relaxation of regulations, such as those relating to essential health benefits.

-01.jpg)